Kadavumbagam Synagogue, Mattancherry

By Jay A. Waronker

LOCATION

For centuries, Kochi’s Mattancherry was a vibrant center for Jewish life with three synagogues lining Synagogue Lane in Jew Town alongside Jewish schools, homes, and places of businesses. Hundreds of Jews lived, worked, prayed, were educated, played, socialized, and celebrated life-cycle and holiday events here, representing one of India’s and the world’s famous centers of Jewish existence. Although this small area of Kochi has never been exclusively Jewish as Muslims mixed with Hindus, Christians, and those of other persuasions have lived here as well, it was a Jewish enclave by choice where its people existed side by side and interacted on a regular basis. These Jews themselves were never a homogenous community, but descendants of individuals of distinct cultural and social backgrounds who arrived in Kerala at different periods and from disparate places. Eventually they built three synagogues all located within a short walk.

In addition to the Paradesi Synagogue, two others houses of prayer once co-existed in the heart of Jew Town: the now demolished Tekkumbagam Synagogue almost immediately to the south of the Paradesi Synagogue on the west side of the street, and the Kadavumbagam Synagogue. These latter buildings served the local Malabari Jews for centuries, and both closed in 1955 when their congregations immigrated en masse to Israel. The Kadavumbagam Synagogue is also located directly on Jew Street (or Synagogue Lane), less than a ten minute walk from the Paradesi Synagogue and just south of the main intersecting lane that leads east to the water front and jetty where the passenger ferry docks. Cross the intersection and soon look for the derelict building mid-block on the west (right) side of the street. It gets its name from its location; in Malayalam, kadavu means landing place and bagam means side.

HISTORY

A portion of the former Kadavumbagam Synagogue still stands today and can easily be seen from the road, but it has been compromised over time and the building, first rented and then sold to non-Jews after the congregation left for Israel, today sits idle and is padlocked. Over the years the former synagogue has changed hands, and the structure has served as a warehouse or sat empty. When a stretch of Jew Street running in front the building was altered some time in the 1960s, Kadavumbagam Synagogue’s two story gatehouse and the connecting breezeway behind it were demolished. Today the only portion of the former synagogue compound still standing is the sanctuary building. In recent decades, this remaining structure and its tight surrounding courtyard has been poorly maintained. At the time the road was shifted and straightened, other buildings in the immediate area were likewise affected, so it is no longer possible to experience the former synagogue is in original context.

The early history of the Kadavumbagam Synagogue is unclear. A local narrative indicates that it was established as early as 1130, and the name was taken from a synagogue that existed in Cranganore. Oral stories reveal that the synagogue was built in 1400 when Jews abandoned the nearby Kochangadi Synagogue just south of Jew Town (yet historically this did not happen until 1795), that it was ruined, and then rebuilt by the mudaliyar (community leader of the Kerala Jews) Baruch Levi in 1539 (Joshua: 1) or that his son, Joseph David HaLevy, was responsible for beginning its construction. In 1549, the synagogue was completed by Yaakov ben David Castiel, the brother of Elihu Shmuel Castiel, the third mudaliyar and father of David Yaakov Castiel, the fourth mudaliyar (Spalak: 57). Another source offers a slightly different history in that in 1539/40 the building of the Kadavumbagam Synagogue was begun, and it was completed by Barukh Joseph Levi who had restored the Kochangadi Synagogue. It was, in turn, extended or restored in 1549 by Jacob David Castiel (Segal: 31).

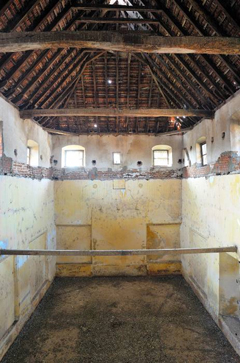

Enough of the Kadavumbagam Synagogue remains standing to recognize it as a quintessential example of vernacular Kerala architecture for its materials, construction technique, massing, and details. In response to the climate and annual monsoons and drawing from locally available natural resources and regional construction practices, the building features a steeply sloped clay tiled roof with deep, open eaves that are set on rafters crafted of local wood. The roof framing system is supported by load bearing walls made of hand-cut laterite stone blocks quarried from the region that are veneered with chunam, a polished lime plaster. Although many of them have now been removed and filled in, large wooden windows and doors with transoms and shutters once punctured the synagogue’s thick walls, providing natural light and ventilation to the inside.

The road and adjacent buildings in the immediate area of the former synagogue have changed since the congregation left Mattancherry in the mid-1950s, yet there was once an open space directly across from the synagogue compound which extended east to the nearby water and provided a view of the landing place for boats traveling southward. In years past, according to a narrative, the Rajah of Cochin would set sail in private boat from his Dutch Palace (built by the Portuguese to honor the Rajah and his royal house and upgraded during the Dutch period) at the northern end of Jew Town just beyond the Paradesi Synagogue. Whenever his Highness was about to travel southward and pass the Kadavumbagam Synagogue, news would reach the congregation. Someone would open the doors of the gatehouse (today missing), those of the sanctuary with its azara (anteroom) in front of the sanctuary, and finally the doors of heckal itself, which, in Kerala synagogue tradition, were often all on a longitudinal axis. The Rajah’s boat would pause at the landing, offering him a clear vista from the water, across to the shore, through the gap between neighboring buildings towards the synagogue and all the way through the spaces of the building to the end point: the Sefer Torahs. According to this tradition, the Rajah of Cochin would then stand and prostrate himself towards the synagogue (Johnson: 129).

In its prime, the Kadavumbagam Synagogue was notable for its exterior ornamentation and painted surfaces, specifically at the gabled facade of the sanctuary building. The interior was also unique to other Kerala synagogues for its elaborately carved woodwork. Though the majority of Kerala synagogues featured ceilings and balconies made of wood with detail drawing from the region’s secular and religious building traditions using timber, the ones at Kadavumbagam were the most intricate. About four decades after the building was left behind by the departing congregation, the synagogue’s interior finishes were purchased and carefully removed through funding by an English Jew, shipped to Jerusalem, and then meticulously restored by the Israel Museum. Today the reconstructed room represents Asian synagogues in the museum.

The Kadavumbagam Synagogue is also notable for many miracles attributed to it while it was in use. According to a local legend, whenever anyone, even unscrupulous characters or people of others religions, became sick, sought protection, safety, or misplaced something and sought to recover it, or when a woman was soon to give birth or just thereafter, it was customary to bring a gift or donation to the synagogue as well as to pray for good will. These associations attached to the synagogue were widely known to the local community and far beyond (Johnson: 129).

CURRENT STATUS

Today the Kadavumbagam Synagogue, much altered but still identifiable, a gabled building from the front with its flaked walls and steel roll-up door, can easily be overlooked beside more intact neighboring historical architecture, including a few former Jewish residences with their prominent Magen Davids (Stars of David) on the exteriors. Seeing at it today offers little suggestion of its former glory, yet the Kadavumbagam Synagogue was once an attractive building.

Offered for sale as of 2010, the former synagogue is locked and difficult to access. For those that are particularly persistent, shop owners in the immediate area may be able to contact the owner for a look inside.

CITED SOURCES

Johnson, Barbara C. and Daniel, Ruby. Ruby of Cochin: An Indian Jewish Woman Remembers. Philadelphia and

Jerusalem: The Jewish Publication Society, 1995.

Joshua, Isaac. The Synagogues of Kerala 70 CE to 1988, unpublished, 1988.

Segal, J. B. The History of the Jews of Cochin. London: Vallentine Mitchell, 1993.

Spalak, Orpha. The Jews of India: A Story of Three Communities. Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 1995.